For a while, the default AI strategy was simple: add a chatbot to everything.

One big assistant on the marketing site. Another inside the app. Maybe one in the help center. Same general idea everywhere: a single, general-purpose AI you could ask anything.

That model is already starting to age out.

Across the industry, AI is getting smaller, more specialized, and more tightly embedded in specific workflows. Providers like OpenAI, Anthropic, Mistral, and others now ship families of models, including smaller, cheaper options designed for focused tasks rather than open-ended conversation.

Analysts expect the same pattern inside products. Gartner projects that about 40% of enterprise applications will include task-specific AI agents by 2026, up from less than 5% today.

That shift has huge implications for UX. Instead of designing around one “catch all” chatbot, teams need to think in terms of small, embedded agents that handle very specific jobs inside a larger system.

This is where UX, information architecture, and system design really start to matter.

Why One Big Chatbot Usually Disappoints

The idea of one assistant that can “do everything” sounds efficient. In practice, it creates problems for both users and teams:

- Too much cognitive load. Users have to guess what the bot can do, how to phrase requests, and where the limits are. There is no clear mental model.

- Unclear responsibility. When an assistant is responsible for everything, it is not really responsible for anything specific. It becomes hard to trust it with high-stakes tasks.

- Awkward UX patterns. A chat window is not always the best interface for tasks like configuring a quote, reviewing a design, or reconciling financial data.

- Limited guardrails. It is harder to set clear constraints, audit behavior, or explain decisions when one system touches every surface.

Gartner even calls out “agentwashing” as a problem, where basic assistants are branded as agents without real autonomy or clear scope.

Users feel that gap. They do not want to negotiate with a generic chatbot every time they need to complete a focused task. They want tools that feel purpose-built.

The Rise of Small, Specialized Agents

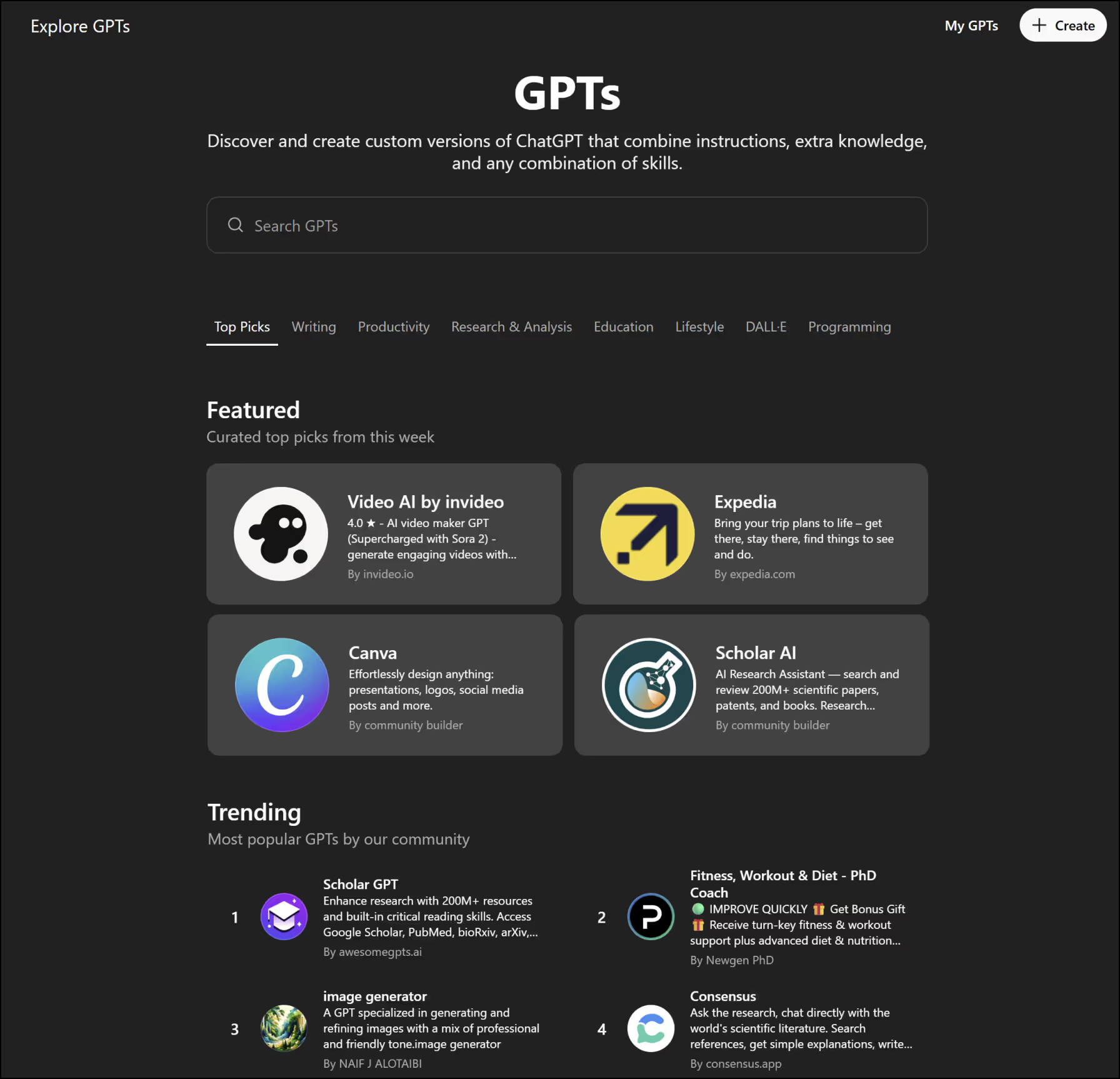

Instead of one giant assistant, many products are moving toward networks of smaller agents that each handle something specific.

That might look like:

- A “quote builder” agent that pulls pricing, discounts, and terms into a draft proposal.

- A “design QA” agent that checks a layout for accessibility issues, spacing inconsistencies, or missing states.

- A “research triage” agent that clusters customer feedback and flags patterns for a UX team.

- A “data anomaly explainer” that walks an analyst through why a metric suddenly moved.

On the infrastructure side, the tools are catching up to this pattern. OpenAI, for example, offers smaller and cheaper models like GPT-4o mini that are explicitly positioned for focused, high volume tasks, not just general chat.

Open-source trends are similar. Commentators point out that 2024 was a turning point for smaller models, with ongoing work in 2025 and beyond to push performance and efficiency on the edge rather than relying only on giant models in the cloud.

Analysts are already talking about “agent ecosystems” rather than single assistants.

From a UX perspective, that means we are not designing for one AI anymore. We are designing for a cast of them.

What This Shift Means for UX

When you move from one big chatbot to many small agents, UX stops being about “where do we put the chat bubble” and becomes a systems problem.

A few key implications:

1. UX moves from conversations to task flows

Most useful agent interactions are not long back and forth chats. They are small, focused flows:

- A button that says “Generate first draft” inside a CMS.

- A panel that suggests three alternative headlines based on the current page.

- A sidebar that answers clarifying questions about a complex form.

- A review step where an agent flags potential issues before publishing.

These are micro-UX patterns, not separate destinations. Users should feel like the agent is built into the workflow, not bolted on as a side chat.

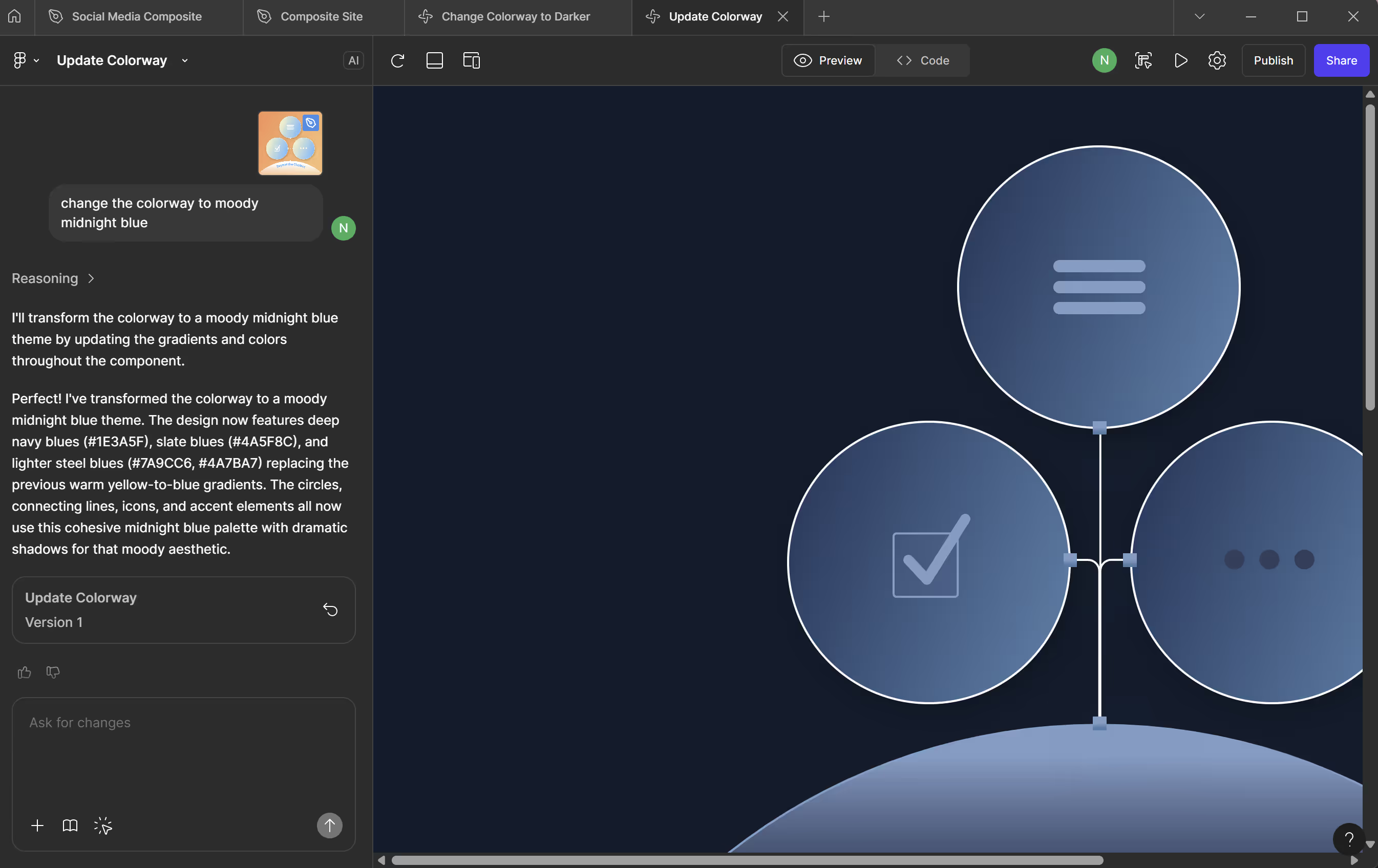

2. Agents become part of the interface, not “somewhere else”

In older patterns, teams would add an “Ask AI” area or a floating chat icon. With multiple agents, the better approach is to embed AI where it is contextually relevant.

For example:

- In a design system dashboard, a small “Check this component” action might invoke a QA agent.

- On a pricing configuration screen, an “Explain this calculation” link might call a calculation agent.

- Inside a research repository, a “Summarize this cluster” control might call a synthesis agent.

Each agent has a clear trigger, clear inputs, and clear outputs. Users do not need to guess.

3. Transparency and boundaries become essential

Small agents only work if users understand what they do and what they do not do.

That means:

- descriptive labels, not just “Ask AI”

- short explanations of scope, such as “Reviews this layout for WCAG color contrast issues”

- visible limits, such as “This agent cannot send emails or change live data”

- consistent patterns for how agents show results, errors, and uncertainty

These are UX and content design problems as much as engineering problems.

Designing Agent Ecosystems, Not Isolated Features

Once you have more than one agent, you need to think about the system they operate in.

Some practical questions UX and product teams should answer:

- What are the defined roles for each agent?

- How do agents relate to each other? Do they hand off work, or stay isolated?

- Do they share a tone of voice and visual language?

- How do you show users which agent they are interacting with?

- What happens when agents disagree or fail?

Agentic design frameworks are already starting to document patterns for multi-agent handoffs, orchestration, and transparency.

From a design perspective, this is similar to building a modular design system. You are defining repeatable patterns for:

- how agents are invoked

- how they explain themselves

- how they present results

- how they escalate to humans

The goal is to reduce surprise. Users should not feel like every agent is a brand new personality with a different attitude and behavior.

Why Structure and Webflow-Style Systems Matter Here

Small agents are only as good as the structures they plug into.

They need:

- clean, semantic HTML that makes it clear what is a heading, what is a label, and what is content

- predictable components that agents can read and interact with

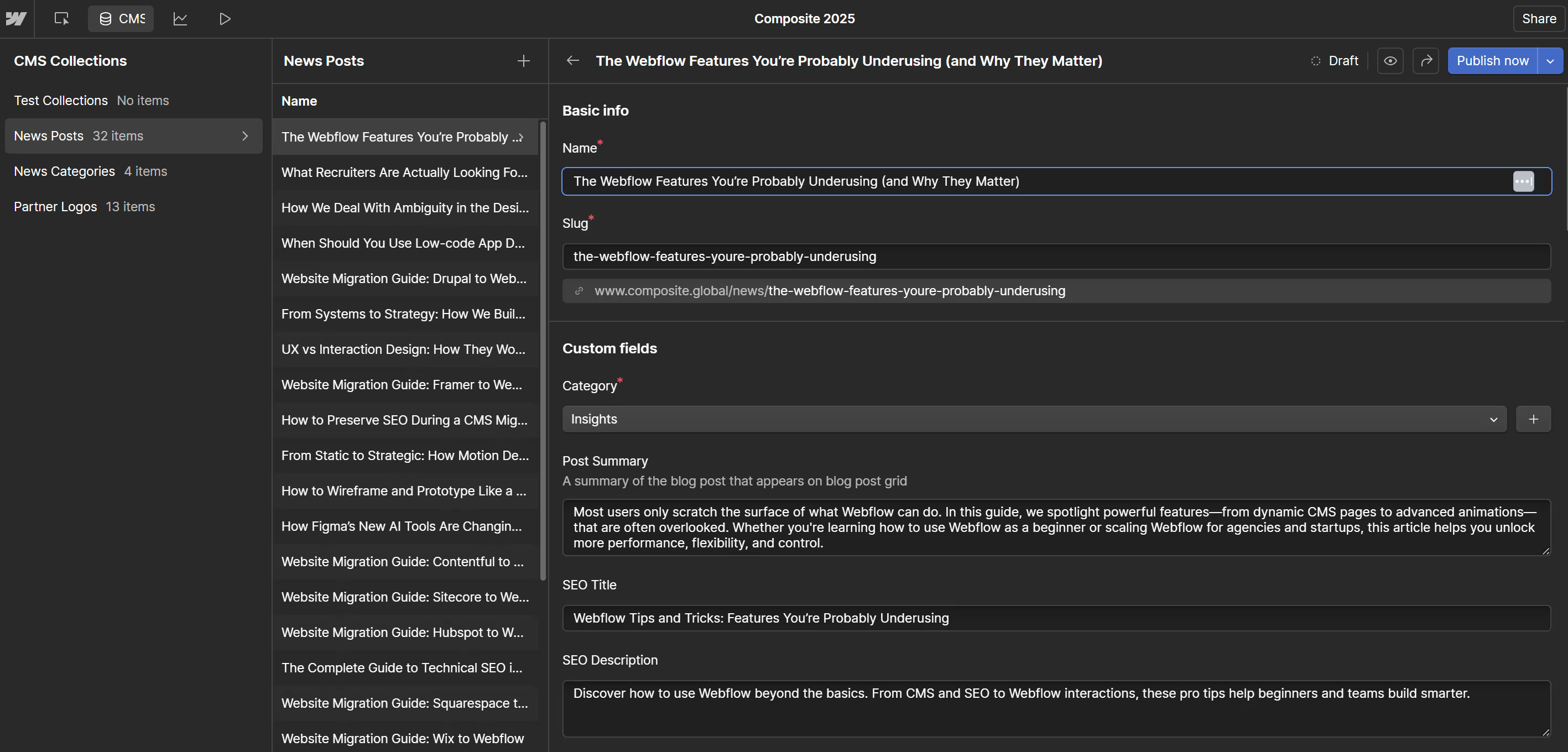

- well-defined CMS fields that separate “title”, “summary”, “body”, “author”, and so on

- clear relationships between pages, such as case studies, service lines, and blog articles

These are exactly the kinds of systems a good Webflow agency or web development agency focuses on.

On a platform like Webflow, you can:

- build component libraries that keep patterns consistent across the site

- define CMS collections that give agents structured, labeled data to work with

- enforce typography, spacing, and hierarchy so both humans and models can understand the layout

- layer in schema markup to give answer engines and agents additional context

That matters whether you are a web design agency in New York working on marketing sites, or a UX design agency designing tools and dashboards. If the underlying structure is messy, any agent layered on top will have a harder time making useful decisions.

How Brands Can Start Using Small Agents in a Responsible Way

You do not need a full agent ecosystem on day one. A practical way to start is:

- Find friction in existing workflows.

Where do people copy-paste between tools, re-calculate the same logic, or ask the same questions? - Define a narrow job for an agent.

Something like “draft the first version of this email based on the brief” or “flag missing fields before publishing”. - Design the UX first, not the prompt.

Decide where the agent appears, how it is triggered, what users see before and after, and how they can recover from a bad result. - Document the agent’s responsibilities.

Treat it like a teammate. What is it good at? What should it never do? When should a human review? - Test with real users.

Not just for accuracy, but for trust, comprehension, and control.

If you already have a modular homepage or a component-driven design system, you are in a strong position. You can introduce agents into specific modules without reinventing the entire experience.

From Chatbots to Agent Networks

The move from a single, catch-all chatbot to a network of small, well-defined agents is not just a technical evolution. It’s a design evolution. And it requires teams to rethink how their digital systems are structured.

As analyst reports have pointed out, many AI projects fail not because the models are weak, but because the surrounding experience is unclear. When the architecture is confusing, the workflows are ambiguous, or the content is unstructured, even the most capable agent will struggle to make reliable decisions. The inverse is also true: when the environment is legible, constrained, and predictable, small agents become far more valuable.

This is why UX and information architecture matter so much in the shift ahead. An agent can only be as effective as the system it belongs to. If the interface is inconsistent, the taxonomy is vague, or the outputs aren’t governed, users won’t trust the agent—even if the underlying model is impressive. But when the roles are clear, the patterns are consistent, and the boundaries are explicit, agents start to feel like part of the product rather than an experiment layered on top.

The most successful teams won’t be the ones chasing the newest model announcements. They’ll be the ones designing environments where AI can operate with clarity: modular components, well-structured content, stable workflows, and predictable handoffs between humans and agents. In that kind of system, small agents don’t compete with each other or duplicate effort. They collaborate. They reinforce the overall architecture. They help users move through tasks more smoothly.

The era of “one big chatbot that does everything” is already fading. What comes next is a cast of specialized assistants, each with a clear purpose, each embedded directly into the product experience. And the organizations that invest in structures with clean IA, modular design, and intentional UX will be the ones ready to take advantage of it.