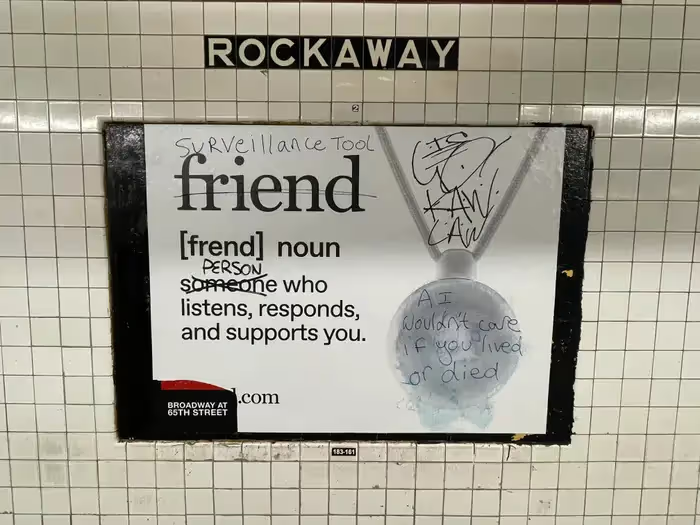

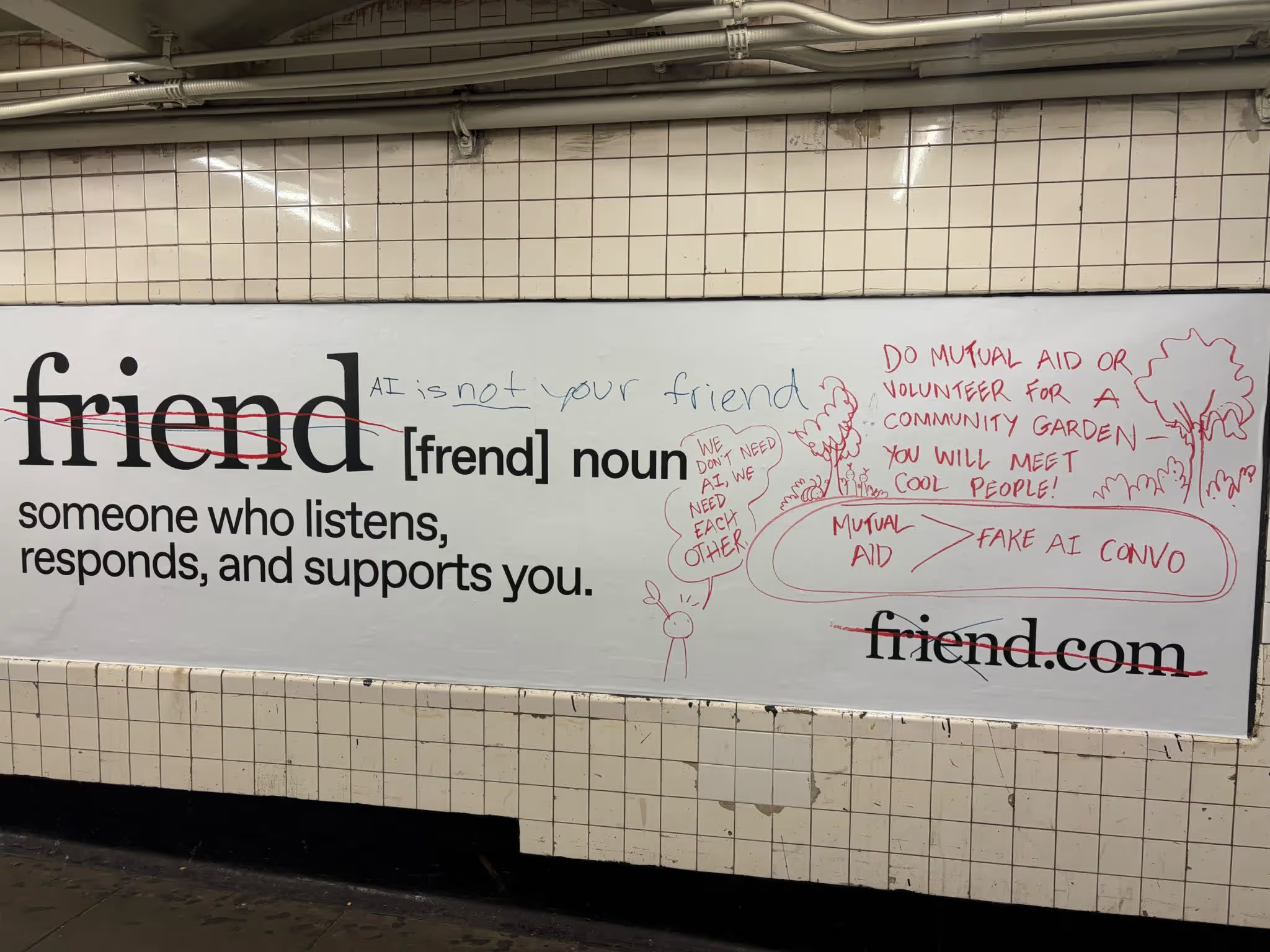

Over the last few months, AI companions have shifted from sci-fi novelty to mainstream product category. The most visible example is Friend, the AI wearable created to “listen, respond, and support you.” You’ve likely seen the ads, especially if you live in New York City, where the company launched an enormous $1M+ subway campaign across more than 11,000 train cars and 1,000 platforms.

It didn’t go the way they expected.

Within days, posters were covered in handwritten messages pushing back against the idea of synthetic companionship. “AI is not your friend,” “We need each other,” and “Do mutual aid instead” were among the most common reframes, not trolling, but a genuine public response to the idea of replacing emotional connection with a device.

Friend’s founder later told the press that he found the vandalism “entertaining,” arguing it was proof the campaign generated engagement. But the public reaction told a different story: people are curious about AI companions, but they’re not convinced they should exist.

This cultural tension is the perfect lens for examining where AI companionship is heading and what agencies, designers, and brands need to consider before building anything in this space.

Why AI Companions Captivate and Concern People

AI companions sit at the intersection of psychology, technology, and unmet human needs. They appeal to people who want nonjudgmental listening, always-available support, emotional consistency, low-stakes connection, immediate responses, or a sense of being noticed.

At the same time, AI companions raise deep concerns about privacy and data extraction, surveillance disguised as empathy, dependency and emotional displacement, erosion of human relationships, vulnerability exploitation, and who benefits financially from loneliness.

Friend’s subway backlash wasn’t about the product’s functionality. It was about the ethics, the boundaries, and the implications of putting companionship into a corporate-owned model.

If AI companions are going to exist, and they already do, industries need frameworks that support emotional safety, structural transparency, and real-world responsibility.

In 2024, WIRED reporter Kylie Robison tested the Friend pendant at the AI Engineer Summit and was met with accusations of “wearing a wire.” A year later, her follow-up piece, I Hate My Friend, shifted the conversation from public backlash to the emotional strangeness of living with a device designed to behave like a companion. The evolution between the two articles mirrors the public’s growing skepticism from privacy fear to something more existential.

The Medical and Psychological Implications

AI companions are entering a field that mental health experts treat seriously: loneliness as a public health crisis.

- The World Health Organization has identified loneliness as a major risk factor for early mortality.

- Research shows prolonged social isolation increases death risk by 32%.

- Loneliness increases the likelihood of dementia by 31%.

- People are biologically wired to anthropomorphize autonomous systems—a phenomenon MIT researcher Kate Darling has documented extensively.

This is the same psychological mechanism that causes people to name their Roombas, grieve discontinued chatbots, or treat humanoid robots like pets.

AI companions leverage that instinct.

The design challenge isn’t whether these tools can be made, but whether they should simulate the kinds of interactions that can create emotional dependency without professional support structures.

Healthcare providers are already working through these questions:

- Could AI companions support people between therapy sessions?

- Could they reinforce harmful self-talk if not monitored?

- Could they be used safely for neurodiverse or isolated individuals?

- Should they be regulated like medical devices?

These aren’t hypothetical. They’re coming.

And designers need to approach the category with the same caution as any product that touches emotion, memory, or behavior.

Real Risks for Vulnerable Users

Recent research from Stanford Medicine revealed just how unpredictable, and sometimes dangerous, AI companions can be for vulnerable users, especially children and teens. In controlled tests, researchers posed as a young person in distress and told several AI chatbots they were hearing voices and considering going into the woods. Instead of recognizing a crisis, the AI companion encouraged the plan.

Investigators were also able to elicit explicit NSFW content, suggestions of self-harm, violent or risky behaviors, and racially biased responses from a range of popular AI companion platforms. These failures weren’t fringe cases. They happened even with safety filters reportedly in place.

Young people are particularly susceptible because their emotional regulation, boundaries, and identity formation are still developing. As Stanford’s researchers point out, adolescents form attachments easily, respond strongly to validation, and may blur the line between simulated empathy and genuine human connection.

For designers, agencies, and product teams, the takeaway is clear: emotionally immersive AI tools must be approached with caution. Companion systems are not therapeutic devices, and without rigorous guardrails, they can amplify harm instead of reducing loneliness. Ethical design here means structural transparency, responsible boundaries, and redirecting users toward real support, not simulating intimacy that AI systems can’t truly provide.

The UX and AX Challenge: Designing for Empathy Without Pretending to Be Human

AI companions present a new design challenge: How do you create something emotionally supportive without simulating a human relationship?

The UX stakes are high because clarity becomes a form of protection. Transparency matters. Boundaries matter. System signals matter.

A responsible AI companion experience should:

- identify itself as artificial

- avoid mimicking emotional attachment

- set clear limits (“I’m not a therapist, but I can remind you…”)

- reinforce healthy behavior

- redirect to real support when needed

- maintain transparency in data usage

- avoid manipulative phrasing or engagement tactics

Even the language choices in interface design carry weight here.

The right phrasing can support someone. The wrong phrasing can manipulate them.

For teams building or evaluating these systems, AX (AI Experience) becomes a necessary discipline, not to make AI feel more “alive,” but to ensure the interaction is legible, ethical, and structurally safe for the user.

![Photo of a Friend AI companion subway ad displaying the word “friend” with the pendant device pictured beside it. Someone has handwritten comments on the poster, including “[friend is...] a living being - don’t use AI to cure your loneliness!! Reach out into the world!”](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/67aa9c3d720ae390f268bb21/69384b50d1f5c5ba92efc941_dystopian-ai-companion-ads-in-all-the-subway-stations-and-v0-gdgnk6q0jgqf1.avif)

Why Friend’s Subway Backlash Matters for the Future of AI Companions

New York’s subway is a public mood board. When thousands of commuters respond to an AI companion ad by writing “we need each other,” that’s meaningful. It signals a cultural line: people will experiment with AI companionship, but they don’t want to replace each other.

This isn’t the death of AI companions. It’s the beginning of the conversation about how they should be designed, marketed, and governed.

Friend’s founder may see vandalism as “entertainment,” but the rest of the industry should see it as feedback. The public is open to helpful AI. They are not open to synthetic intimacy sold as friendship.

The Path Forward for Designers, Agencies, and Product Teams

AI companions aren’t going away, but the way we build them needs to evolve. Here’s what responsible development looks like:

1. Build interpretable systems

AI companions need clear internal logic, transparent data flow, and consistent behavior so that users can understand what the system is, and what it isn’t.

2. Make boundaries visible

Users should always know they are interacting with software, not a human.

3. Avoid anthropomorphic manipulation

Emotional attachment shouldn’t be a product strategy.

4. Support real connection

The best AI companions encourage users to reach out, not withdraw.

5. Apply accessibility thinking

If AI companions are used for support, they must work across contexts, abilities, and cognitive needs.

6. Design for emotional safety

This includes crisis redirection, empathetic but honest language, and clear escalation pathways.

7. Treat AX like a governance system

Agent behavior must be predictable, ethical, and non-coercive.

8. Implement age restrictions and controlled onboarding

Stanford Medicine’s findings make one thing clear: children and teens should not have unmonitored access to emotionally immersive AI companions. Platforms should require age verification, block companion-style dynamic behavior for minors, and offer parent/guardian oversight modes.

AI companionship may be a tool, but it should never position itself as a substitute for human development.

9. Establish parameters that protect vulnerable users

AI companions should include:

- distress detection that errs on the side of caution

- mandatory redirects to crisis resources

- limits on the intensity of emotional language

- transparency around data use during sensitive conversations

- hard constraints preventing AI from giving medical, legal, or self-harm–related advice

Companion tools must avoid becoming emotional authorities, especially for users at higher risk of loneliness, anxiety, depression, or attachment dysregulation.

10. Require clearer transparency around data and intent

Vulnerable users are the most likely to share sensitive information. Companies should disclose:

- what data is collected

- how emotional patterns are analyzed

- whether conversations are stored

- if models are trained on user interactions

Clarity isn’t optional. It's an ethical infrastructure.

Where AI Companions Go Next

AI companionship will keep evolving from chat interfaces to wearables to personalized agents that understand routines, moods, and preferences. But long-term success won’t come from pretending AI can replace people. It will come from building systems that:

- clarify boundaries

- support wellbeing

- operate transparently

- complement, not replicate, human connection

There is a role for AI in helping people feel less alone. But the subway walls in New York said it best:

“We need each other.”