We’ve all done it—that split-second decision to hit “Accept All” on a cookie banner because you just want to read the article. It’s one of the most universal UX moments online: a reminder that convenience usually beats caution. But in 2025, as AI-driven systems become more personal and data-hungry, privacy isn’t just a checkbox anymore. It’s a user experience challenge.

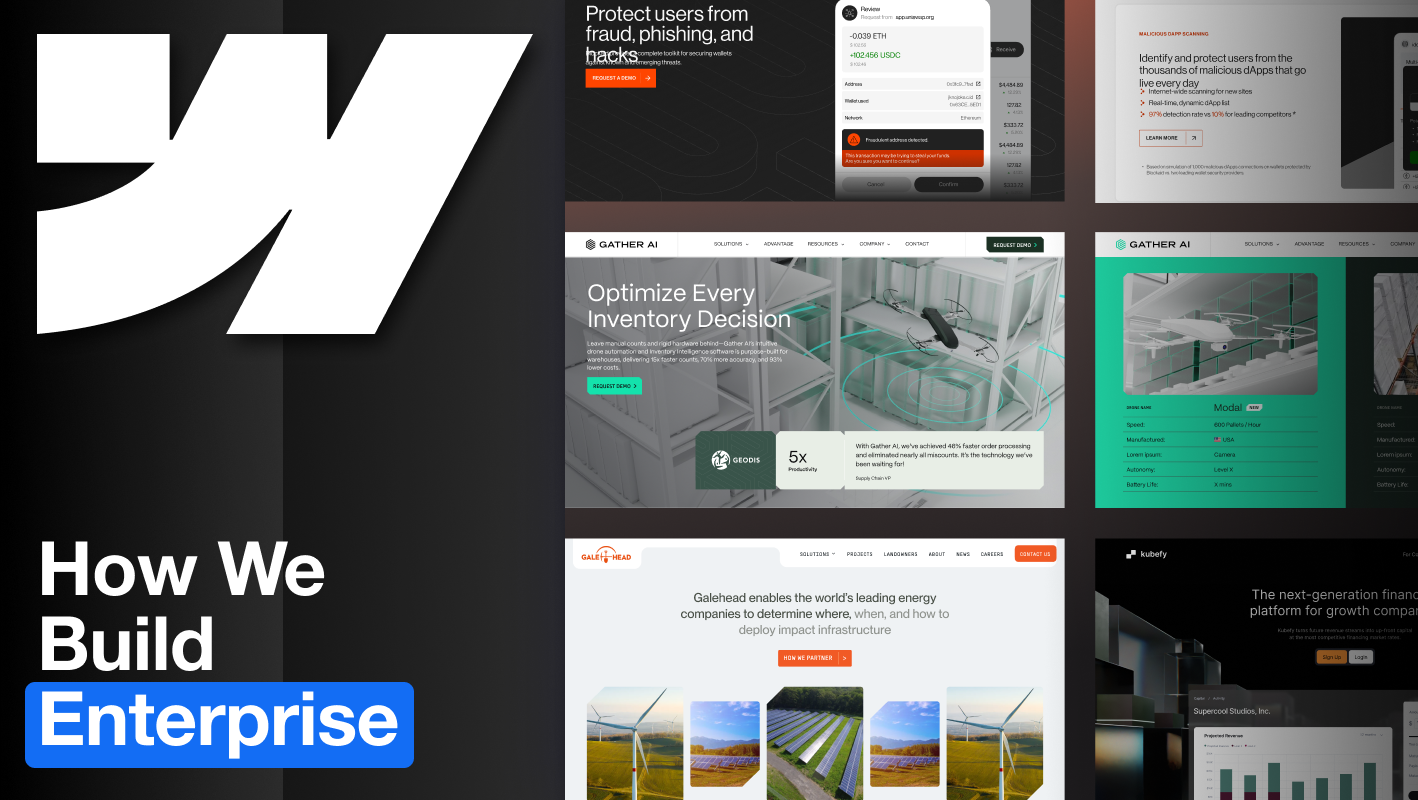

Transparent privacy design isn’t just good ethics, it’s good website optimization. The clearer your consent flows and cookie policies, the faster users engage and the more trustworthy your brand feels.

Designers are starting to treat privacy as part of the journey, not just a legal sidebar. And that shift, from compliance to empathy, might be the biggest quiet revolution happening in UX right now.

From “Don’t Get Sued” to “Don’t Break Trust”

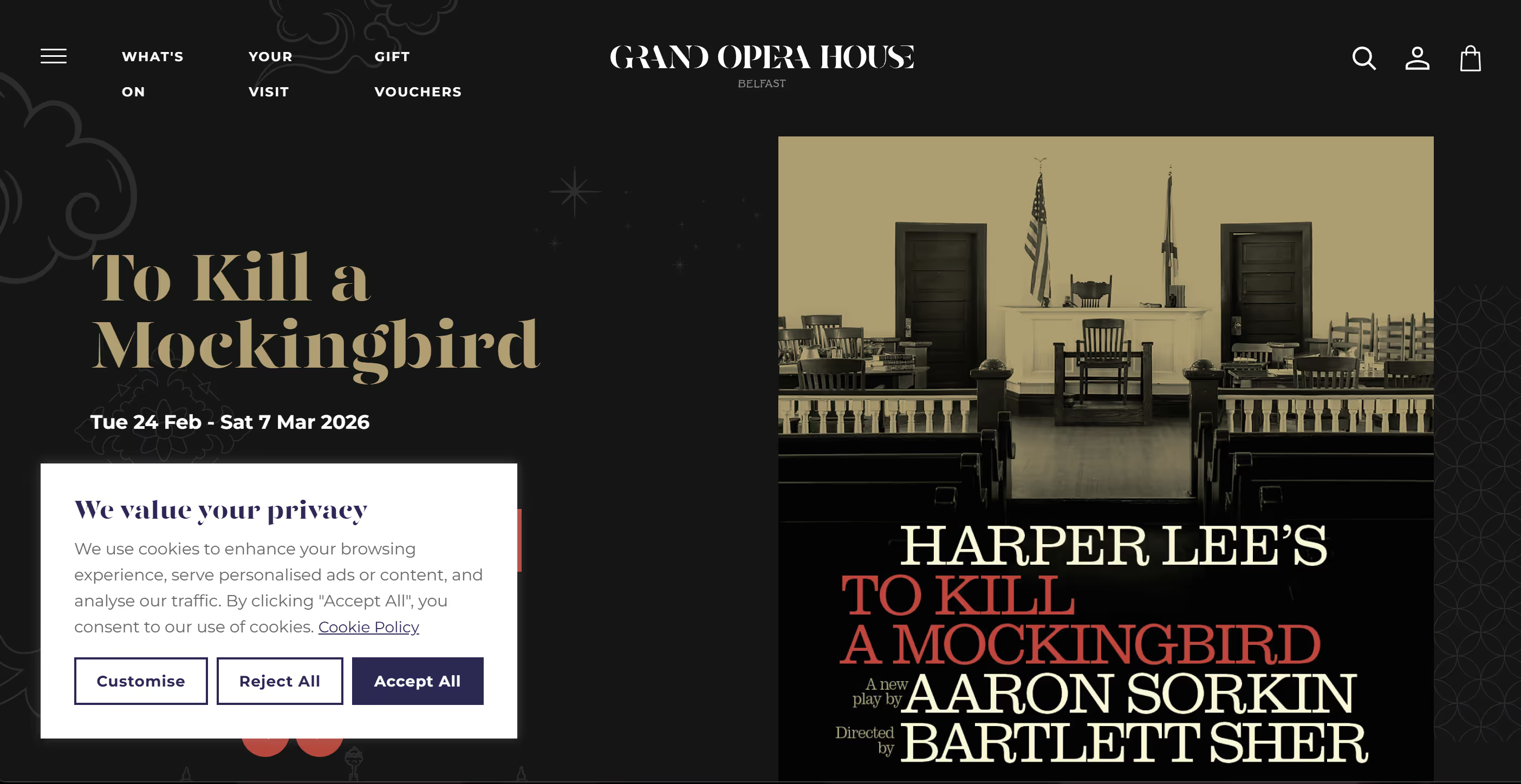

For years, privacy design was a reactive space. Companies built experiences around what regulators demanded, not what users actually felt. The result? Legalese-riddled modals, endless opt-outs, and that small army of “Manage Preferences” buttons we all ignore.

But things are changing. As products become more integrated with AI, health data, and behavior tracking, the emotional side of privacy has come into focus. People aren’t just asking “What data are you collecting?” They’re wondering “Why do you need it, and how will it help me?”

The UX question is no longer how to hide privacy behind consent walls, but how to design trust into the flow and how to make users feel like their data is respected before they even think to ask.

The Rise of Privacy Personas

If traditional personas tell us who users are, privacy personas reveal how they feel about being known. An emerging idea in UX research circles is designing with multiple privacy mindsets in mind. For example:

- The Convenience-First User: They just want things to work and don’t mind sharing data if it saves them time.

- The Cautious Optimist: They’re open to personalization but need transparency and reassurance.

- The Privacy Maximalist: They’ll ghost your site if they can’t use it without handing over an email.

Each group experiences privacy differently, and their comfort levels can change depending on context. Think medical data versus shopping history, for instance. Good UX design meets each of these people halfway, offering clarity, control, and calm without making them dig for it.

Just like in b2b content marketing, privacy messaging needs segmentation. What resonates with a developer isn’t the same language that builds trust with a healthcare client or end consumer.

Designing for Privacy Without Saying “Privacy”

The best privacy design doesn’t feel like privacy design. It feels like clarity.

When done right, users aren’t thinking about the policies in the footer, they’re just moving through an experience that feels transparent, honest, and optional.

A few small choices make a huge difference:

- Micro-copy that informs, not intimidates. (“We only use this to personalize your dashboard” > “Your data may be processed for service optimization.”)

- Visual hierarchy that makes consent easy. Equal buttons for “Accept” and “Decline,” not one bold, one invisible.

- Contextual disclosure. Tell users what’s being tracked when it matters, not three pages deep in a policy.

It’s empathy in interface form: acknowledging that people want control without forcing them to become privacy lawyers. Writing privacy language that feels human is a form of content optimization where every word impacts whether users feel informed or pressured.

Empathy as a Design Skill

Empathy has always been a buzzword in UX, but when it comes to privacy, it’s measurable. Every decision you make about visibility, defaults, or data hierarchy communicates your values.

An example: an AI tool that displays why it’s recommending something, not just the result, instantly feels more trustworthy. A finance app that explains how it protects your account before asking for access feels safer. These are emotional cues that build trust quietly, without a legal team hovering nearby.

It’s also where ethical foresight comes in by thinking about how a feature could be misused, not just how it will be used. This type of anticipatory design is becoming a marker of maturity in UX teams.

Data as a Relationship, Not a Transaction

Data collection used to be a one-way street: users give, companies take. Now, users expect something in return like personalization, convenience, and/or transparency.

That exchange is a relationship, and like any relationship, it’s built on boundaries. Good design reinforces those boundaries through tone, clarity, and pacing. Instead of “you agreed to this,” it feels like “you chose this.”

Some of the best examples of empathic privacy design aren’t loud at all, they’re in the quiet details: a confirmation screen that shows exactly what was saved, a dashboard where users can delete their own history, or a loading state that explains what’s happening instead of masking it.

Trust is built in milliseconds, but it’s maintained through ongoing clarity.

Designing for the Post-Consent Era

We’re entering what some call the post-consent era of UX—a world where users can’t reasonably read every policy, and AI systems make decisions faster than any checkbox can keep up.

That doesn’t mean consent disappears, it means design becomes the new consent form.

The interfaces themselves must feel respectful. They need to communicate, through tone and structure, that users are in control, even when they’re not thinking about privacy explicitly.

It’s not about building walls around data, it’s about building windows. Transparency doesn’t have to mean exposure, it can mean visibility with dignity.

Tip: Consider adding privacy UX to your site audit checklist: Are cookie banners accessible? Do users have real choices? Are analytics tools clearly explained?

The Takeaway

Privacy-driven UX isn’t about scaring people with compliance or hiding behind fine print. It’s about designing for human comfort in a digital world that knows too much.

As designers, writers, and builders, we’re shaping how people experience trust online. The next generation of UX won’t be defined by how fast users can click “Accept,” but by how confident they feel doing it.

Because in the end, empathy is the best privacy policy we’ve got.